I have voluntourism in my Google Alerts, so that I can get links to press releases, news articles that mention the term. I’m not fond of voluntourism, where volunteers pay large amounts of money to go abroad for a few weeks, or even several weeks, to engage in a short-term activity that will give them a sense of helping people, animals or the environment. I look at this growing industry with great skepticism in terms of actually helping anyone, because it’s focused on the wants of the volunteer – that feel-good, often highly photogenic experience – not the critical local needs of local people or the environment, and there’s little screening of volunteers – most everyone is taken, so long as they can pay. What these foreigners bring through these voluntourism programs is often not skills, experience or capabilities that cannot be found locally – it’s money, and I see no evidence that this money benefits local people – maybe the people that run the program are “helped”, but not those meant to be helped by the volunteers. I don’t think all pay-to-volunteer schemes are horrid, and I don’t think creating a vacation that has a social or environmental “good” goal (transire benefaciendo) is a bad thing, but I think there are a tremendous number of voluntourism programs out there that aren’t really benefitting communities in the developing world – and some are actually causing harm. I push back to questions about and posts prompting voluntourism on Quora and Reddit, and I’ve been pleased to see more and more people doing the same. That push-back must be working, because now I’m also seeing a lot of voluntourism companies aggressively fighting back on the blogosphere, asserting that their programs are worthwhile (but never offering hard data to prove it).

I have voluntourism in my Google Alerts, so that I can get links to press releases, news articles that mention the term. I’m not fond of voluntourism, where volunteers pay large amounts of money to go abroad for a few weeks, or even several weeks, to engage in a short-term activity that will give them a sense of helping people, animals or the environment. I look at this growing industry with great skepticism in terms of actually helping anyone, because it’s focused on the wants of the volunteer – that feel-good, often highly photogenic experience – not the critical local needs of local people or the environment, and there’s little screening of volunteers – most everyone is taken, so long as they can pay. What these foreigners bring through these voluntourism programs is often not skills, experience or capabilities that cannot be found locally – it’s money, and I see no evidence that this money benefits local people – maybe the people that run the program are “helped”, but not those meant to be helped by the volunteers. I don’t think all pay-to-volunteer schemes are horrid, and I don’t think creating a vacation that has a social or environmental “good” goal (transire benefaciendo) is a bad thing, but I think there are a tremendous number of voluntourism programs out there that aren’t really benefitting communities in the developing world – and some are actually causing harm. I push back to questions about and posts prompting voluntourism on Quora and Reddit, and I’ve been pleased to see more and more people doing the same. That push-back must be working, because now I’m also seeing a lot of voluntourism companies aggressively fighting back on the blogosphere, asserting that their programs are worthwhile (but never offering hard data to prove it).

I’ve been happy to see the tide turning against many forms of voluntourism as people realize that work abroad should make local people the number one priority, not the feel-good experience for a foreign volunteer. For instance, Australian NGOs are refusing to place volunteers in orphanages abroad, because of the exploitation of children, potential harm to children, and lack of any data showing such voluntourism helps children at all.

The UK’s International Citizen Service (ICS), which has placed thousands of young people in volunteer roles around the world, is now under scrutiny: Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO) has taken action against ICS and other members of the UK consortium of organizations providing volunteering opportunities over safety concerns. The UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), according to a report by VSO, regarded ICS as a “high-risk programme due to the security and safety issues” involved. “ICS safeguarding incidents have included death by drowning of two volunteers, sexual assaults, and the detention of volunteers by local police.” Volunteers live and work in countries where they may be exposed to petty and violent crime, political instability, endemic diseases and natural disasters.

There’s even a growing backlash against medical voluntourism, per reporting by Noelle Sullivan, a member of the faculty in global health studies at Northwestern University, who says her research shows that some people volunteering abroad for a few weeks, or several weeks, to engage in medical “help” for people in developing countries “does indeed cause harm.

It must be taking its toll, because I got a link to a press release about how a certain African “foundation” has hired a PR agency “to change the public perception of medical volunteering or voluntourism.” I’m not going to link to the press release – no free publicity here for a for-profit marketing company. But I had a look at the “foundation”‘s web site. The site is mostly about the gorgeous “luxury” accommodations for volunteers on a game reserve, whcih has an onsite gym, an infinity pool, a private patio “for stargazing,” and nearby opportunities for hiking, mountain biking, golfing, weight training, yoga, abseiling, white river rafting, tubing, kloofing, microlighting, helicopter rides, “and hot air ballooning!” The company can hook volunteers up with wildlife photography tours and photography courses, half day trips to an animal rehabilitation center “featured on National Geographic,” and visits for “pampering yourself at the local spas.” I’m surprised there aren’t workshops provided on how to take the perfect “Look how I’m helping these poor people” selfies… Oh, there is a page or two about the medical services volunteers will squeeze into their busy schedule enjoying all that hiking and hot air ballooning.

Update: a blog from 2015, where animal “help” becomes animal “torture”

“The ‘turtle conservation program’ was shut down after the police came (there is a law in Fiji to protect turtles as they are threatened by extinction). A girl made a… ehh… Let’s say critical Facebook post. I think ‘inhuman’ and ‘animal torture’ were some of the words she used… I’m just glad that I got my money back without any problem because I know about 7 people who had to go to court to get some of their money back because the agencies made a lot of great promises without keeping them. What they offer is not really volunteer work, here they call it voluntourism. A lot of money which doesn’t actually help anybody but just finances the international agencies. I got quite disillusioned about volunteering here. I left the volunteer house as soon as possible and went to a resort. The turtles were set free, but they are probably dead because they have been in the tank for too long and weren’t able to survive anymore. I’m so sorry for them.”

Also see:

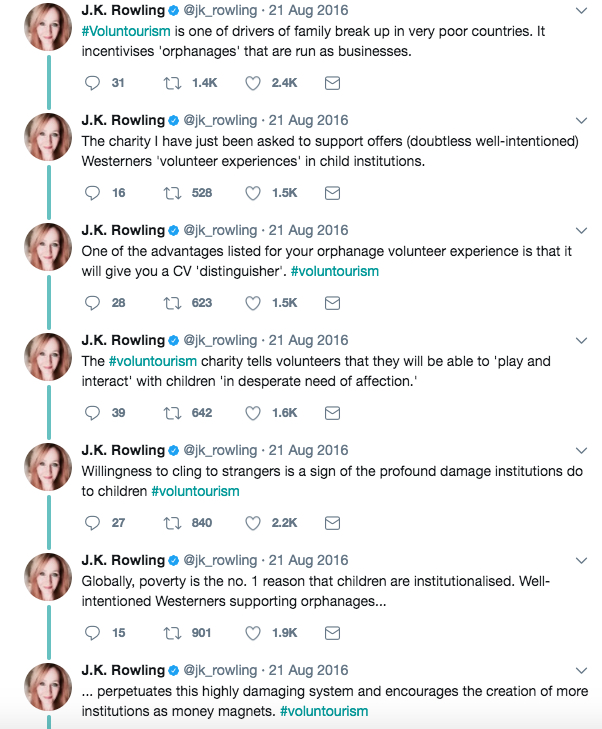

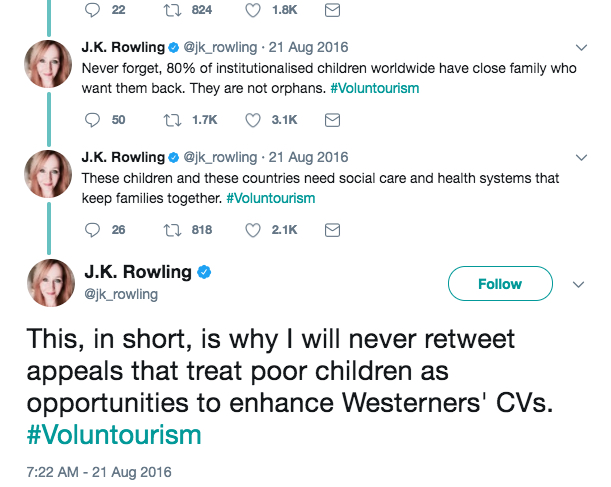

- J.K. Rowling speaks out against orphan tourism

- Medical Voluntourism Can Cause Serious Harm

- The harm of orphanage voluntourism (& wildlife voluntourism as well)

- Promises & Pitfalls of Global Health Volunteering

- The harm of orphanage voluntourism (& wildlife voluntourism as well)

- What effective short-term international volunteering looks like

- voluntourism: use with caution

- In defense of skills over passion

- Vanity Volunteering: all about the volunteer

- humanitarian stories & photos – use with caution

- Vetting Organizations in Other Countries

- Safety in International Volunteering Programs

- Hosting International Volunteers

- Realistic tips for volunteering abroad

- Problems in countries far from home can seem easy to solve