Volunteer recruitment has always been easy for me. Often, when I post an assignment to a third-party platform like VolunteerMatch on behalf of whatever nonprofit I’m working for, I end up having to take it down two days later, because I get plenty of candidates to choose from.

I try to craft volunteer roles in a way that will benefit the volunteer (enhance or show-off skills, give them an opportunity to be involved directly in a cause, maybe even have fun). I also am explicit about why the task is important to the organization and those we serve. And I’m detailed in the role description of exactly what the expectations are in terms of time commitment and deadlines.

I also almost always get to make a commitment to involving volunteers in my work at a nonprofit – if I’m working for a nonprofit that already involves volunteers. I don’t involve volunteers in my work because “I have all this work to do and I can’t afford an assistant.” I do it because I think volunteers might be the best people for a task – like when I need more neutral eyes, when I need people who might be more critical in surveying participants or in reviewing the data they are compiling than a paid person. I do it because I think non-staff should get to see how a nonprofit works in a transparent, first-hand way – and I think those people turn into amazing advocates back out in the communities around the organization.

Sometimes, other staff see these volunteers involved in my work and are inspired to involve more volunteers in their work too. But they often just see “free labor” and want to treat VolunteerMatch like Task Rabbit: we’ve got work to do, let’s find someone to do it – for free!

I once had a staff person ask if I would recruit a new volunteer for her to serve food and then clean up after a breakfast meeting. I said no. At this particular organization, I believed strongly that every volunteering opportunity should include an emphasis on the volunteer learning what the nonprofit did, who it served and why the nonprofit was needed. Serving food and washing dishes didn’t do that. I also felt like involving volunteers in this way would contribute to the idea that so many staff members have at that organization: volunteers are free and do stuff we don’t want to do. I also didn’t like the idea of board members thinking of the “other” volunteers as merely waitresses and dishwashers.

It’s not a black or white issue: if someone contacted me and said, “I urgently need volunteering hours for court-ordered community service,” I might offer them that waitressing and dishwashing volunteer gig, knowing how hard it is for them to get the hours they need, but I would also offer all the other volunteering opportunities we have available as well and, if the volunteer was qualified, consider them for other, more significant roles too.

If this was a big fundraising event for the nonprofit, I might feel differently about having volunteers staffing the coat check, making sure there is plenty of coffee and helping clean up – but I would recruit the event-support volunteers from the ranks of our current volunteers, and those volunteers would be identified to all attendees: “We want to let you know that the staff you see here helping you all have a great experience here tonight are some of our volunteers. These are the volunteers who work with our clients, work on our web site, edit videos for us, research grants for us, etc. They are students, web designers, lawyers, job seekers, etc. They are here tonight, as volunteers, to further show their support for our organization and we encourage you to talk to them about what they do as volunteers for our organization.”

Why am I so concerned with the appropriateness of volunteer roles? The titles alone on these blogs and web pages that I have written should explain why – but if they don’t, then you’ll need to read them:

- Mission statements for your volunteer engagement (Saying WHY your organization or department involves volunteers)

- Initiatives opposed to some or all volunteering (unpaid work), and online and print articles about or addressing controversies regarding volunteers replacing paid staff

- Resources re: labor laws and volunteering.

- Make volunteering transformative, not about # of hours

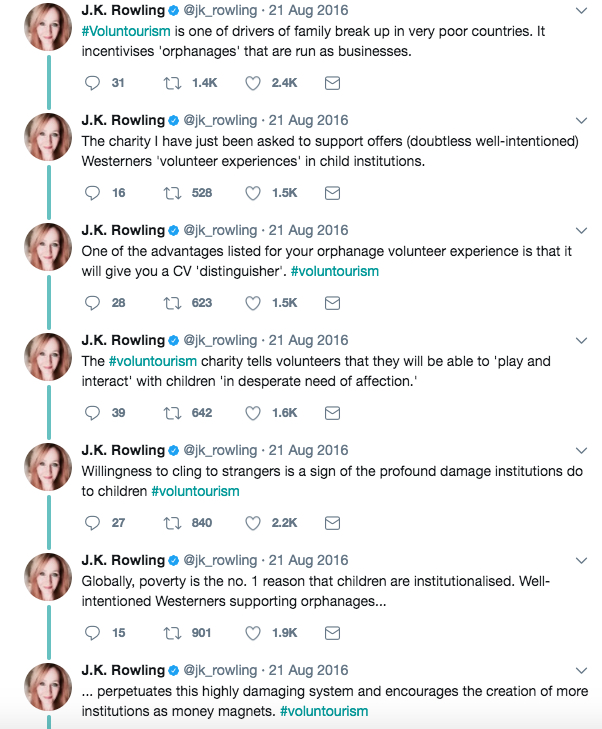

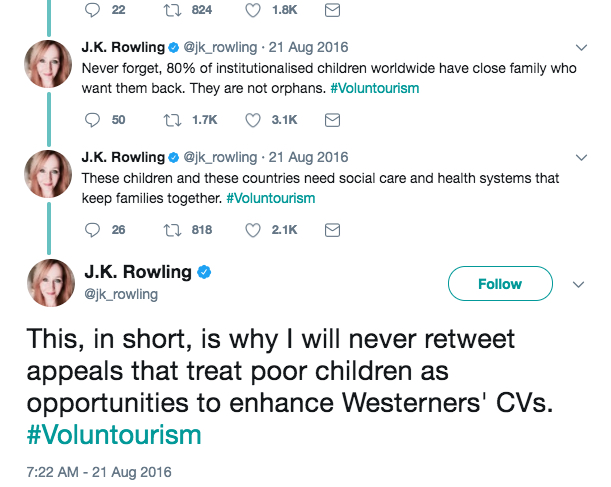

- Vanity volunteering: all about the volunteer

- UN Agencies: Defend your “internships”

- Advice for unpaid interns to sue for back pay

- Fight against unpaid internships will hurt volunteering

- It’s real: the unpaid internships & volunteers controversy

- EU agencies exploiting interns?

- When to NOT pay interns, redux

- Pizzeria tries to recruit unpaid interns, feels Internet’s wrath

- Do NOT say “Need to Cut Costs? Involve Volunteers!”

- Another anti-volunteer union

- Volunteers are suing!

- Growing misconceptions about the role of nonprofits in the USA

- Why Should the Poor Volunteer? It’s Time To Re-Think the Answer

- tasks for a university intern at your organization

If you have benefited from this blog or other parts of my web site and would like to support the time that went into researching information, developing material, preparing articles, updating pages, etc. (I receive no funding for this work), here is how you can help.