Looks like an interesting read for those in the nonprofit sector and other mission-based organizations, and a great resource of quotes for various program and funding proposals – maybe even interviews with the press to explain why a nonprofit is doing whatever it is it is doing.

Looks like an interesting read for those in the nonprofit sector and other mission-based organizations, and a great resource of quotes for various program and funding proposals – maybe even interviews with the press to explain why a nonprofit is doing whatever it is it is doing.

At $150, I’ll have to beg my way into an academic library in order to read it…

Edited by Emma M. Seppälä, Emiliana Simon-Thomas, Stephanie L. Brown, Monica C. Worline, C. Daryl Cameron, and James R. Doty

How do we define compassion? Is it an emotional state, a motivation, a dispositional trait, or a cultivated attitude? How does it compare to altruism and empathy? Chapters in this Handbook present critical scientific evidence about compassion in numerous conceptions… and contribute importantly to understanding how we respond to others who are suffering… it explores the motivators of compassion, the effect on physiology, the co-occurrence of wellbeing, and compassion training interventions. Sectioned by thematic approaches, it pulls together basic and clinical research ranging across neurobiological, developmental, evolutionary, social, clinical, and applied areas in psychology such as business and education. In this sense, it comprises one of the first multidisciplinary and systematic approaches to examining compassion from multiple perspectives and frames of reference.

Here’s the table of contents:

Preface

James R. Doty

Part One: Introduction

Chapter 1: The Landscape of Compassion: Definitions and Scientific Approaches

Jennifer L. Goetz and Emiliana Simon-Thomas

Chapter 2: Compassion in Context: Tracing the Buddhist Roots of Secular, Compassion-Based Contemplative Programs

Brooke D. Lavelle

Chapter 3: The Empathy-Altruism Hypothesis: What and So What?

C. Daniel Batson

Chapter 4: Is Global Compassion Achievable?

Paul Ekman and Eve Ekman

Part Two: Developmental Approaches

Chapter 5: Compassion in Children

Tracy L. Spinrad and Nancy Eisenberg

Chapter 6: Parental Brain: The Crucible of Compassion

James E. Swain and S. Shaun Ho

Chapter 7: Adult Attachment and Compassion: Normative and Individual Difference Components

Mario Mikulincer and Phillip R. Shaver

Chapter 8: Compassion-Focused Parenting

James N. Kirby

Part Three: Psychophysiological and Biological Approaches

Chapter 9: The Compassionate Brain

Olga M. Klimecki and Tania Singer

Chapter 10: Two Factors that Fuel Compassion: The Oxytocin System and the Social Experience of Moral Elevation

Sarina Rodrigues Saturn

Chapter 11: The Impact of Compassion Meditation Training on the Brain and Prosocial Behavior

Helen Y. Weng, Brianna Schuyler, and Richard J. Davidson

Chapter 12: Cultural neuroscience of compassion and empathy

Joan Y. Chiao

Chapter 13: Compassionate Neurobiology and Health

Stephanie L. Brown and R. Michael Brown

Chapter 14: The Roots of Compassion: An Evolutionary and Neurobiological Perspective

C. Sue Carter, Inbal Ben-Ami Bartal, and Eric C. Porges

Chapter 15: Vagal pathways: Portals to Compassion

Stephen W. Porges

Part Four: Compassion Interventions

Chapter 16: Empathy Building Interventions: A Review of Existing Work and Suggestions for Future Directions

Erika Weisz and Jamil Zaki

Chapter 17: Studies of Training Compassion: What Have We Learned, What Remains Unknown?

Alea C. Skwara, Brandon G. King, and Clifford D. Saron

Chapter 18: The Compassion Cultivation Training (CCT) Program

Philippe R. Goldin and Hooria Jazaieri

Chapter 19: From Specific to General: The Biological Effects of Cognitively-Based Compassion Training

Jennifer Mascaro, Lobsang Tenzin Negi, and Charles L. Raison

Part Five: Social Psychological and Sociological Approaches

Chapter 20: Compassion Collapse: Why We Are Numb to Numbers

C. Daryl Cameron

Chapter 21: The Cultural Shaping of Compassion

Birgit Koopman-Holm and Jeanne L. Tsai

Chapter 22: Enhancing compassion: Social psychological perspectives

Paul Condon and David DeSteno

Chapter 23: Empathy, compassion, and social relationships

Mark H. Davis

Chapter 24: The Class-Compassion Gap: How Socioeconomic Factors Influence Compassion

Paul K. Piff and Jake P. Moskowitz

Chapter 25: Changes Over Time in Compassion-Related Variables in the United States

Sasha Zarins and Sara Konrath

Chapter 26: To Help or Not to Help: Goal Commitment and the Goodness of Compassion

Michael J. Poulin

Part Six: Clinical Approaches

Chapter 27: Self-Compassion and Psychological Well-being

Kristin Neff and Christopher Germer

Chapter 28: Compassion Fatigue Resilience

Charles R. Figley and Kathleen Regan Figley

Chapter 29: Compassion Fears, Blocks and Resistances: An Evolutionary Investigation

Paul Gilbert and Jennifer Mascaro

Part Seven: Applied Compassion

Chapter 30: Organizational Compassion: Manifestations Through Organizations

Kim Cameron

Chapter 31: How Leaders Shape Compassion Processes in Organizations

Monica C. Worline and Jane E. Dutton

Chapter 32: Compassion in Healthcare

Sue Shea and Christos Lionis

Chapter 33: A Call for Compassion and Care in Education: Toward a More Comprehensive ProSocial Framework for the Field

Brooke D. Lavelle, Lisa Flook, and Dara G. Ghahremani

Chapter 34: Heroism: Social Transformation Through Compassion in Action

Philip G. Zimbardo, Emma Seppälä, and Zeno Franco

Chapter 35: Social Dominance and Leadership: The mediational effect of Compassion

Daniel Martin and Yotam Heineberg

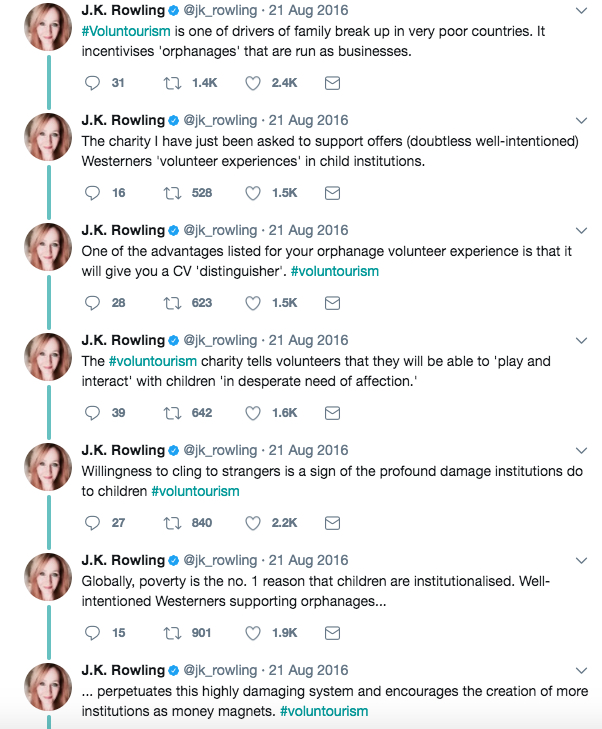

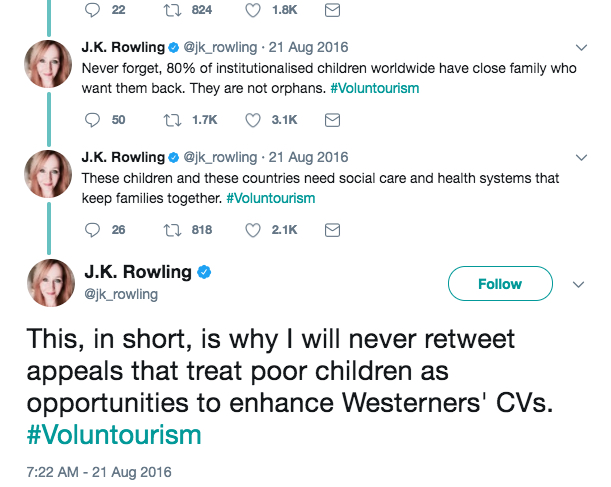

This, in short, is why I will never retweet appeals that treat poor children as opportunities to enhance Westerners’ CVs. #Voluntourism

This, in short, is why I will never retweet appeals that treat poor children as opportunities to enhance Westerners’ CVs. #Voluntourism