In a recent blog hosted by the Scientific American, Noelle Sullivan, a member of the faculty in global health studies at Northwestern University, says her research shows that some people volunteering abroad for a few weeks, or several weeks, to engage in medical “help” for people in developing countries “does indeed cause harm. In fact, the international volunteer placement industry opens the door to potentially disastrous outcomes.”

In a recent blog hosted by the Scientific American, Noelle Sullivan, a member of the faculty in global health studies at Northwestern University, says her research shows that some people volunteering abroad for a few weeks, or several weeks, to engage in medical “help” for people in developing countries “does indeed cause harm. In fact, the international volunteer placement industry opens the door to potentially disastrous outcomes.”

Empirical data about the medical voluntourism industry is sparse, but Sullivan does have solid data: “I’ve studied medical volunteering in Tanzania since 2011, including over 1,600 hours observing volunteer-patient interactions across six health facilities. I have spoken with more than 200 foreign volunteers in Tanzania, plus conducted formal interviews with 48 foreign volunteers and 90 hosting health professionals.

She notes a variety of voluntourism web sites that invite volunteers with little or no medical training to do invasive procedures abroad, including providing vaccines, pulling teeth, providing male circumcisions, suturing and delivering babies. “Most volunteers I’ve observed deliver at least one baby, despite being unlicensed to do so.”

Her examples in the article are stunning: in Tanzania in 2015, her team encountered a young woman that’s called Mary in her article:

Mary routinely delivered babies unassisted by local midwives because she appeared familiar with the procedure—a skill she said she learned in 2013 on a previous volunteer stint.

Mary violated obstetrics best practices, doing unnecessary episiotomies (cutting the skin between the vaginal opening and anus to make room for the baby’s head) and pulling breech babies (babies positioned bottom instead of head-first in the birth canal). Once routine in obstetrics, current guidelines restrict episiotomy to exceptional cases because they may cause permanent problems for the mother, including incontinence. Meanwhile, pulling breech babies can cause suffocation.

After Mary’s departure, we learned she was not a medical student at all; she was an undergraduate student, unaware of the risks in what she was doing.

Voluntourism – where volunteers pay large amounts of money to go abroad for a few weeks, or even several weeks, to engage in a short-term activity that will give them a sense of helping people, animals or the environment – is a growing industry. I look at most of it with great skepticism in terms of actually helping anyone, because it’s focused on the wants of the volunteer – that feel-good, often highly photogenic experience – not the critical local needs of local people or the environment, and there’s little screening of volunteers – most everyone is taken, so long as they can pay. What these foreigners bring through these voluntourism programs is often not skills, experience or capabilities that cannot be found locally – it’s money.

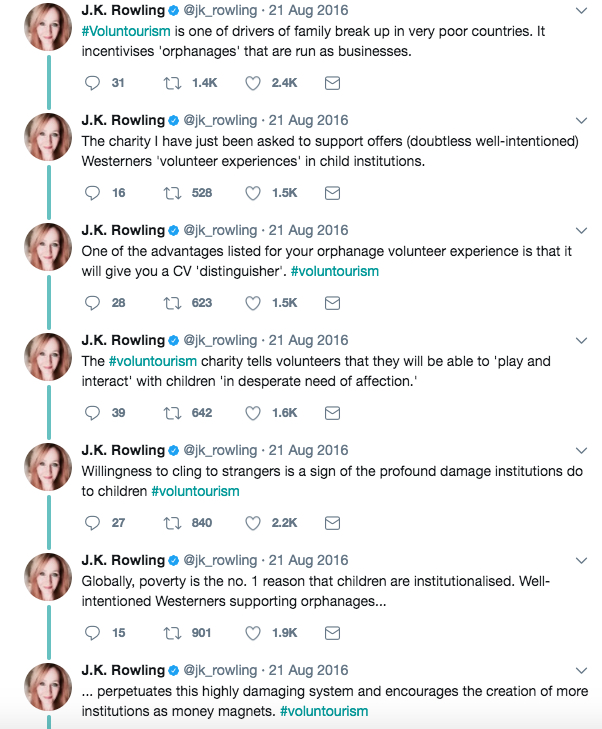

The End Humanitarian Douchery campaign takes a much stronger stand against voluntourism in any form than I do, drawing attention to the negative consequences such can have for local communities in particular. The campaign organizers offer tips on “how to find a program that will have a truly POSITIVE impact on the host community.” Likewise, ‘Looks good on your CV’: The sociology of voluntourism recruitment in higher education, an academic paper by Colleen McGloin of the University of Wollongong, Australia and Nichole Georgeou, of Australian Catholic University, says that “voluntourism reinforces the dominant paradigm that the poor of developing countries require the help of affluent westerners to induce development. And this article is advice from someone who paid to volunteer abroad – and realized she shouldn’t be. All are worth reading, no matter where you stand on the issue of voluntourism or volunteering abroad.

I do think there are some effective short-term pay-to-volunteer abroad programs, among them Bpeace and Humanist Service Corps. But both of these programs are driven by what local people want, and they do NOT take just any volunteer that can pay.

This is my reality check regarding volunteering abroad, which reviews all the different types of programs. It links to many articles that discuss the dangers of voluntourism programs to local people, and to volunteers themselves, and to quality advice on how to make a real difference abroad.

July 17, 2017 update: Charities and voluntourism fuelling ‘orphanage crisis’ in Haiti, says NGO. At least 30,000 children live in privately-run orphanages in Haiti, but an estimated 80% of the children living in these facilities are not actually orphaned: they have one or more living parent, and almost all have other relatives, according to the Haitian government.

Also see “More harm than good? The questionable ethics of medical volunteering and international student placements” by Irmgard Bauer in Tropical Diseases, Travel Medicine and Vaccines, volume 3, Article number: 5 (2017)

April 11, 2018 update: Goats and Soda, a program on National Public Radio about news in the developing world, has an editorial about medical tourism. “Doctors and medical students are flocking to programs where they spend a couple of weeks to months volunteering in what’s called a ‘low-resource’ country. In these places, medical expertise and technology may lag behind richer nations. And sometimes their eagerness to help can have unintended negative consequences.” The official name of such programs is the “short-term clinical experience in global health” — which goes by the clunky acronym of STEGH. These overseas volunteers can end up doing harm: Perhaps a doctor performs a surgery, then goes home. The patient develops complications, and there’s no local health-care worker who can help them. Or maybe the visiting medical professionals offer free care that takes business away from local docs. Medical students might want to try a surgery they wouldn’t be able to do in the U.S. because they haven’t had enough training. Medications that are provided for these docs may be past their expiration date. And students sometimes are oblivious to local customs — say, that women dress modestly or a physician should not touch a patient of the opposite sex. Dr. Lawrence Loh, adjunct professor at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health, has researched and published widely over the past decade on the ethics of short-term volunteering abroad. he notes in the article: “Medical missions, if not conducted with the local community, represent another form of cultural colonialism.” Regarding the problem of trainees overstepping their skill set, he notes, “The golden rule is if you can’t do it in North America, you probably can’t do it over there.” He stresses the importance of having faculty overseeing medical student volunteers. “We need to get away from the idea of parachuting into communities without consulting with local hospitals and clinicians.” The American College of Physicians has issued a position paper on “ethical obligations” for these medical volunteers, both doctors and students. Published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, the paper has been widely praised — but critics have also raised one major concern — no one from the developing world was part of the committee preparing the guidelines. Read the entire editorial about medical tourism here.

November 2019 update: Just found this resource – a 2014 paper, Medical voluntourism in Honduras: ‘Helping’ the poor? by Sharon McLennan of Massey University in New Zealand. It’s based on qualitative research with medical voluntourists in Honduras. The research found that while ostensibly helpful, volunteer tourism in Honduras is often harmful, entrenching paternalism and inequitable relationships; and that many voluntourists are ignorant of the underlying power and privilege issues inherent in voluntourism.” While there are examples of volunteer tourism as both educational and as a form of social action, the paper argues that these are not natural consequences of voluntourism but must be nurtured. As such this paper highlights some implications for practice, noting that addressing the paternalism inherent in much medical voluntourism requires an honest appraisal of the benefits and harm of voluntourism by sending and host organisations, education and consciousness-raising amongst volunteers, and long-term relationship building.

Also see:

Recently, I got asked if I would share a job opening at a PDX (Portland, Oregon)-area nonprofit. It was for a receptionist / volunteer coordinator. I responded:

Recently, I got asked if I would share a job opening at a PDX (Portland, Oregon)-area nonprofit. It was for a receptionist / volunteer coordinator. I responded: