A comment was submitted on one of the most popular blogs I’ve ever written, What online community service is and is not. That blog called out a company that is selling what it calls online community service hours, but which is, in fact, a ruse: customers pay a fee and receive access to videos, which they are supposed to watch, and in return for claiming to watch them, the company gives the “volunteers” a letter from a nonprofit saying they performed online community service. As someone that has been promoting virtual volunteering since the 1990s – and quality standards in all kinds of volunteer engagement – it continues to have me outraged.

A comment was submitted on one of the most popular blogs I’ve ever written, What online community service is and is not. That blog called out a company that is selling what it calls online community service hours, but which is, in fact, a ruse: customers pay a fee and receive access to videos, which they are supposed to watch, and in return for claiming to watch them, the company gives the “volunteers” a letter from a nonprofit saying they performed online community service. As someone that has been promoting virtual volunteering since the 1990s – and quality standards in all kinds of volunteer engagement – it continues to have me outraged.

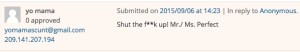

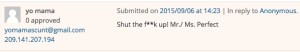

I no longer approve comments on that blog, which has more than two dozen, because, for the last three years, most of the comments I get about this blog are from trolls affiliated with the company, ranting about how I hate hard-working people that don’t have time to do traditional onsite service (a rant that can come only from someone who has not actually read the blog) or name-calling such as this:

Yes, really. Welcome to my world.

But a recent comment from Mark Waterson wasn’t either of those. I didn’t want his comment, and my response, to get buried in the sea of comments on that blog, so the blog entry you are reading now is devoted to this comment.

Mark says in his blog comment:

“This article points out online community service options that are legitimate, but really misses the point of why those other organizations exist. If you are doing community service for court, you need an official signed letter of someone in the nonprofit organization who “supervised” you saying you have completed X hours of community service. Your alternatives, while more legitimate, do not offer this, even at a price, and so no one doing court ordered community service can even consider your suggestions as possible alternatives for their purposes.”

Mark is incorrect, however, on this issue. Many of the online volunteering options I recommend on this page DO provide an official signed letter by the nonprofit organization who was assisted by the volunteer, stating how many hours the person gave as an online volunteer. And I have been one of those nonprofit representatives that wrote and signed such a letter for someone doing court-ordered community service through virtual volunteering. As I state on many of my pages for volunteers, a person needs to ask the nonprofit he or she wants to help – whether that nonprofit is down the street or across the country – BEFORE volunteering if staff would be willing to write and sign such a letter. Indeed, many will say no – even for onsite, face-to-face volunteers – but you will find some that will say yes if you keep looking, as I suggest on my pages.

As volunteerism expert Susan Ellis frequently points out, there are very few onsite, traditional volunteering activities where a volunteer is supervised the entire time he or she is performing service. Instead, the volunteers is trained, then given a desk, or a work space and materials, or a phone, or a garbage bag and some gloves, and then they do MOST of their volunteering largely unsupervised. As someone who has been fooled more than a few times by a volunteer sitting at a desk, looking at a computer screen for hours, and pretending to work – and after a day or two, I find out nothing is getting done – I’ve realized that volunteer supervision is much more than eyes-on-the-volunteer, or sign-in sheets at the door.

As Susan and I discuss in The Last Virtual Volunteering Guidebook, there are many ways to supervise online volunteers, to ensure the work is getting done, that the quality of the work is up-to-snuff, and that the volunteer is getting the support he or she needs, such as regular Skype calls, regular emails back and forth, shared work spaces, regular reviews of work to date, etc. In taking those steps, you are going to know very quickly if you are talking to the person actually doing the work.

As Susan and I discuss in The Last Virtual Volunteering Guidebook, there are many ways to supervise online volunteers, to ensure the work is getting done, that the quality of the work is up-to-snuff, and that the volunteer is getting the support he or she needs, such as regular Skype calls, regular emails back and forth, shared work spaces, regular reviews of work to date, etc. In taking those steps, you are going to know very quickly if you are talking to the person actually doing the work.

Could someone fake online volunteering service? Sure, just as people can fake onsite service: hand the volunteer the plastic bag and the gloves, send them down the road to pick up trash, and when they are out-of-sight, a friend brings them a full bag of trash to return to you. Ta da! Or put three volunteers at your information booth, walk away for five hours, and return, not knowing that one of the volunteers paid the others to lie about her time at the table.

Let’s imagine a volunteering scenario: a father gets a DUI and has to do a certain number of hours of community service. He finds a nonprofit that needs 400 photos on Flickr that each need to be tagged with a unique set of keywords, and because each set of keywords is different, it has to be done manually. He signs up to do the work, is accepted to do the work, but his son actually does the work. But here’s the thing: he could also do that as an onsite volunteer: he could go onsite, sit at a desk, and play Tetris until someone passes by, then switch to the Flickr screen and pretend to work until they are gone; meanwhile, his son back at home is actually doing all the work. Here’s a similar scenario: a mom gets assigned court-ordered community service and she signs up to help a nonprofit translate brochures and speeches into Spanish from English. She comes into the nonprofit, sits at a desk, but she plays Scrabble whilst her daughter back home does all the translating.

I think that any volunteer manager of quality would sniff out these scams quickly, through their discussions with the volunteer, review of work, etc. And that would be true of onsite or online volunteers. TMZ implied that Lindsay Lohan faked her virtual volunteering to fulfill court-ordered community service (be sure to scroll down to the comments – yes, I commented) – it would have been so easy for the nonprofit to know if she did the work or not, through basic volunteer management 101 principles.

Does the tiny possibility that a volunteer can fake work done on a computer mean volunteers fulfilling online community service shouldn’t be allowed to do any online work even if it’s supposed to be done onsite at the organization, rather than via their own computer? No more volunteer web site designers, database data inputters, app designers, translators, editors, podcast producers, photo taggers, and on and on, if they are assigned service by the courts? Of course not. Whether this kind of work is being done onsite or online from the volunteers’ home or a nearby library, the likelihood that a volunteer is pretending to do the work while it’s actually a relative or roommate is so tiny, and so easy to sniff out. Fear of what might happen, in this case, isn’t at all justification of not allowing people assigned court-ordered community service to engage in virtual volunteering.

The biggest challenge to court-ordered folks finding virtual volunteering isn’t fear that they will fake their service by having someone else do it; rather, it’s finding virtual volunteering at all. And many nonprofits refuse to work with court-ordered community service folks period, onsite or online. They just don’t love ’em like I love ’em.

Even though I disagree with Mark, I thank him for writing – I’ve been wanting to expand on this issue for a while now.

Also see:

July 6, 2016 update: the web site of the company Community Service Help went away sometime in January 2016, and all posts to its Facebook page are now GONE. More info at this July 2016 blog: Selling community service leads to arrest, conviction

What online community service is – and is not – the very first blog I wrote exposing this company, back in January 2011, that resulted in the founder of the company calling me at home to beg me to take the blog down.

Haters gonna hate, the latest update on Community Service Help and other similar, unethical companies

Community Service Help Cons Another Person, a first-person account by someone who paid for online community service and had it rejected by the court.

Update on a virtual volunteering scam, from November 2012.

Courts being fooled by online community service scams

Online community service company tries to seem legit.

Online volunteer scam goes global

Government agencies and nonprofits HATE my questions on social media. I ask them publicly because, often, I don’t get a response via email – or because I want my exchange with the organization to be public. Questions like:

Government agencies and nonprofits HATE my questions on social media. I ask them publicly because, often, I don’t get a response via email – or because I want my exchange with the organization to be public. Questions like: