Budapest, Hungary is one of my very favorite cities, and not just because I think it has the BEST FOOD IN THE WORLD. Budapest has what I consider the perfect mix of gorgeous history all around and vibrant new ideas from its young people. It feels unique and ancient while also feeling bold and progressive. It’s an energy that both preserves what’s best about a community or country (history, architecture, environment, the arts, etc.) and helps it prosper and move forward, particularly in times of great economic and cultural change.

Budapest, Hungary is one of my very favorite cities, and not just because I think it has the BEST FOOD IN THE WORLD. Budapest has what I consider the perfect mix of gorgeous history all around and vibrant new ideas from its young people. It feels unique and ancient while also feeling bold and progressive. It’s an energy that both preserves what’s best about a community or country (history, architecture, environment, the arts, etc.) and helps it prosper and move forward, particularly in times of great economic and cultural change.

It is with great sadness that I read about efforts by the Hungarian government to shut down the Aurora community centre. “Now, the Aurora, which rents office space to a handful of NGOs — including LGBTQ and Roma support groups — says it has been pushed to the brink of closure by far-right attacks, police raids and municipality moves to buy the building… NGOs are routinely attacked through legal measures, criminal investigations and smear campaigns — something the Aurora told CNN it has experienced first-hand.”

“We wanted to create a safe environment for civil organizations,” said Adam Schonberger, director of Marom Budapest, the Jewish youth group that founded the community center in 2014. “By doing this we became a sort of enemy of the state. We didn’t set out to be a political organisation — but this is how we’ve found ourselves.” Schonberger didn’t think authorities had targeted Aurora because of its Jewish roots. Instead, he put the harassment down to the group’s values of “social inclusion, building civil society and fighting for human rights.”

Here’s Aurora on Facebook. And here is the Aurora’s web site.

I am very partial to these kind of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) – what we call nonprofits in the USA – that help cultivate grassroots efforts, encourage the sharing and exploration of ideas, and help incubate emerging movements and other NGOs. I believe these NGOs can play an important role in helping immigrants assimilate in a country as well and help the country benefit from the talents and ideas these immigrants may bring. I’ve had the pleasure of addressing groups like this in Eastern Europe, and in the USA in Lexington, Kentucky, and I’ve walked away feeling renewed and energized. Add in promotion and celebration of the arts, like Appalshop does in Eastern Kentucky, and I’m ready to pack up and move to a remote town in Eastern, Kentucky.

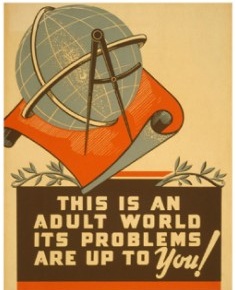

This NGO’s struggles are part of an ongoing shift all over Europe, and indeed, the world, in local and national governments that are rejecting diversity, changing times, dissent and intellectualism, and governing from a place of fear. I could think that I’m isolated from this trend here in the USA, where I’m living these days, but I am not. I remember back in the 1990s, when similar political groups went after arts organizations, even going so far as trying to defund the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) – I helped arrange for Christopher Reeve, a co-founder the Creative Coalition and then performing at a theater where I was working, to debate Pat Robertson about the NEA on CNN’s Crossfire on July 16, 1990, and the theaters where I worked back in those days all felt pressure regarding their artistic choices because of these movements. Those controversies are still here, as any search on Google and Bing shows.

Nonprofits in the USA need to watch carefully what’s happening in other countries and think about how such could happen here. Remember the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN)? It was a collection of community-based nonprofits and programs all over the USA that advocated for low- and moderate-income families. They worked to address neighborhood safety, voter registration, health care, affordable housing and other social issues for low-income people. At its peak, ACORN had more than 1,200 neighborhood chapters in over 100 cities across the USA. But ACORN was targeted by conservative political activists who secretly recorded and released highly-edited videos of interactions with low-level ACORN personnel in several offices, portraying the staff as encouraging criminal behavior. Despite multiple investigations on the federal, state, and county level that found that the released tapes were selectively edited to portray ACORN as negatively as possible and that nothing in the videos warranted criminal charges, the organization was doomed: politicians pounced and the public relations fallout resulted in almost immediate loss of funding from government agencies and from private donors.

There are growing misconceptions about the role of nonprofits in the USA and this could fuel local, state and national movements against nonprofit organizations – not just arts organizations. Nonprofits of every kind need to make sure they are inviting the public and local and state government officials regularly to see their work and WHY their work matters to the entire community, not just their target client/audience. Most nonprofit organizations need to do a much better job using the Web to show accountability. In short: don’t think it can’t happen here.

Also see:

- Could your organization be deceived by GOTCHA media?

- Trump’s War on Volunteerism

- Time for USA nonprofits to be demanding

- A plea to USA nonprofits for the next four years (& beyond)

- Governor Bevin & Donald Trump Are Wrong on Community Service Requirements

- Required Volunteer Information on Your Web Site

- Marketing Your Nonprofit, NGO or small government office Web Site

- capacity building tools & resources for CSO strengthening

I really love this and I would love to see this guide built into all hackathons / hacks4good, the development of apps4good, etc.:

I really love this and I would love to see this guide built into all hackathons / hacks4good, the development of apps4good, etc.: