Each year, the IRS reviews as many as 60,000 applications from groups that want to be classified as tax-exempt.

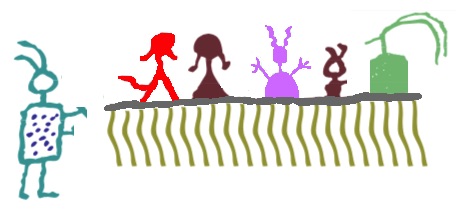

501(c)(4) tax-exempt status is a different nonprofit category than organizations like homeless shelters, arts groups, animal groups, etc. The (c)(4) status allows advocacy groups to avoid federal taxes, just like 501(c)(3) orgs, but the status doesn’t render donations to the groups tax deductible. The primary focus of their efforts must be promoting social welfare – and that can include lobbying and advocating for issues and legislation, but not outright political-campaign activity. Also, these groups do not have to disclose the identities of their donors unless they are under investigation.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s January 2010 “Citizens United” ruling lead to a torrent of new 501(c)4 groups: the number of applications sent to the IRS by those seeking 501(c)4 status rose to 3,400 in 2012 from 1,500 in 2010. MOST of these applications were from conservative groups. And many of these organizations flout the law in terms of not being involved in political-campaign activity – if you saw the whole process where Stephen Colbert oh-so-easily formed his own 501(c)(4) organization, you know what I mean.

So what was the “extra scrutiny” by the IRS? Good luck trying to find out specifics beyond the phrase “extra scrutiny” again and again. It took me an hour on Internet searches to find out enough to make this list of what the “extra scrutiny” was:

- more details on what “social welfare” activities the organizations were undertaking

- speakers they had hosted in meetings

- fliers to promote events

- list of volunteers

- roles/works of volunteers

- lists of members

- list of donors

- positions on political issues the organization was advocating

Some groups have claimed they were asked who was commenting on the group’s Facebook page, but I can’t find any confirmation of this claim.

Of course, this “extra scrutiny” is a fraction of what many of these same people outraged at the IRS were demanding regarding the now defunct nonprofit group ACORN. It’s the same scrutiny these conservatives were screaming about wanting for arts organizations back in the 1990s, in their attempt to eliminate all government funding for arts organizations. And probably most importantly: no organization was prevented from engaging in the activities it wanted to, not even those with pending status. None. Zilch.

This scrutiny is not only what I have been asked for in every nonprofit and government-related job I have held in the last 15 years (yes, I have been asked by a government agency to provide a list of paid staff and volunteers – they wanted to see if our arts organization was involving “enough” volunteers”); these are details I have long encouraged nonprofits to provide on their web sites, to show transparency and credibility.

So, I’ll be by usual blunt self: any nonprofit organization, no matter what their designation, that can’t easily provide details on its programs – who, what, where, when – as well as information the number and role of volunteers and information on any activities that might be considered political advocacy, shouldn’t be a nonprofit. And if that organization is a political group, it should have to provide a public list of all financial donors. Period.

But, no, I’m not going to provide a list of volunteers. Their roles and accomplishments, yes, but not a list of volunteers.

In fact, let’s get rid of (c)(4) nonprofits status altogether. You want to form an organization that engages in political activities? Form a PAC.

My sources:

http://www.politico.com/story/2013/05/israel-related-groups-also-pointed-to-irs-scrutiny-91298.html#ixzz2TSsJpVJ1

http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/05/14/us-usa-tax-irs-idUSBRE94B08I20130514

http://www.southcarolinaradionetwork.com/2013/05/15/at-least-2-sc-tea-party-groups-say-they-were-singled-out-by-irs/

http://www.coyotecommunications.com/outreach/scrutiny.html