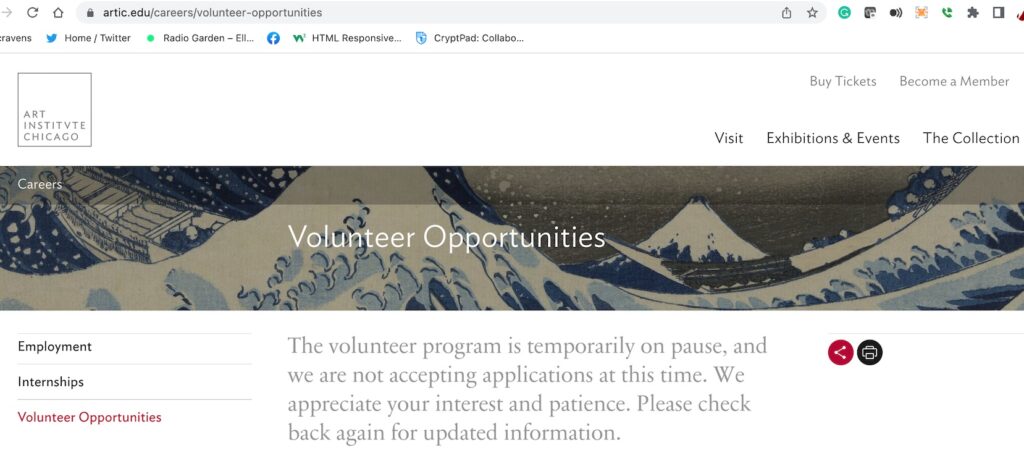

One of the biggest complaints by people that want to volunteer is this: when they express interest in volunteering with a nonprofit, NGO, school, or any community initiative, whether they submit an email, submit an online application, use something like VolunteerMatch or call, they may never get a response, or by the time they do get a response, many weeks or months later, they aren’t available anymore.

On the other side of the equation, lots of people would like to volunteer in a more substantial role than a micro task: they want to really feel like they are making a difference, and they are ready to commit a regular amount of time each week to do that. But they would like to do that from home (virtual volunteering).

A great way to both better serve people that want to volunteer with you and to appeal to those folks looking for a way to volunteer online/remotely in a substantial role is to create a volunteer screening role for a volunteer – or a team of volunteers.

Volunteer screeners:

- Respond to all applicants immediately, to each person who sends an email or an application to express interest. The volunteer screener responds to that email within 48 hours (two business days), asking the person to fill out the application (if the potential volunteers hasn’t already), and asking for additional information, if needed; asking a few follow-up questions via email is a great way to screen out people who aren’t ready to volunteer with you – if they don’t reply, it means they weren’t ready to volunteer.

- Screeners can set up a time to meet initially with each applicant – though remember that you do NOT need to meet with EVERY volunteer applicant: insisting on a phone, web conference or onsite meeting can be an unnecessary barrier to volunteering.

Screeners can ask simple questions to an applicant, via a phone call, an email or a video meeting that helps the screeners gauge if those applicants really understand what the organization is all about, the basic requirements of all volunteer roles, the variety of volunteer roles, etc. The organization can give the screener the final say on whether or not the applicant goes to the next step (the orientation, which can be online, or the training for a particular role) or, the organization can give that power solely to the manager of volunteers, who reads through the profile/evaluation written by the screener and makes the decision (but that manager has to move FAST – lack of response, or a slow response, will result in the volunteer applicant moving on – and feeling like their time so far was wasted).

Screening volunteers should:

- Have a solid understanding of the organization and its opportunities for volunteering, and be able to answer the question, “Why does this organization involve volunteers?”

- Be enthusiastic about the programs of the nonprofit.

- Be able to promptly, immediately input information in a database of volunteer applicant inforamation, even if that database is just a shared spreadsheet.

- Have excellent written communication skills – ability to express ideas and facts clearly – and, perhaps, to also be able to have excellent speaking skills. They may also need excellent online speaking/presentation skills as well.

- Comfortable promptly emailing with, texting with and making phone calls or video calls to applicants.

To get your screeners to that point, you should have a training and a mock interview or screening session, where they get to try out their skills and have a feeling for what interactions with volunteers can be like. And, absolutely, that training can be entirely online.

The organization always needs to know where any volunteer applicant is in the process, the date of that person’s application, the date the applicant was initially screened, etc., so they can know if volunteer applicants are being onboarded quickly. Having applicant information inputted into a shared database is crucial. I’m a board member and in charge of onboarding new applications, and I use a spreadsheet on Google Drive, with the names of every applicant, the date they applied, the date of their interview, if they were going forward after the interview or withdrawing, if they suddenly went incommunicado, etc., and share it with all the other board members, who can view it at any time.

Did you notice that I just described a virtual volunteering role?

And if you want to learn how to avoid the common pitfalls in virtual volunteering and to dig far deeper into the factors for success in creating assignments for online volunteers, supporting online volunteers, and keeping virtual volunteering a worthwhile endeavor for everyone involved, you will not find a more detailed guide anywhere than The Last Virtual Volunteering Guidebook. It’s based on many years of experience, from a variety of organizations. It’s available both as a traditional print publication and as a digital book.

If you have benefited from this blog or other parts of my web site and would like to support the time that went into researching information, developing material, preparing articles, updating pages, etc. (I receive no funding for this work), here is how you can help.