You see the posts on the subreddit regarding volunteerism, on Craigslist, on Quora, on LinkedIn groups, etc.:

You see the posts on the subreddit regarding volunteerism, on Craigslist, on Quora, on LinkedIn groups, etc.:

Come provide care, love and attention to orphans! Help provide daily care to these orphans, help prepare meals, help watch over them, help with homework, participate in playtime activities, and be a child’s best friend in Africa… You’ll also be the shining light for the children and bring about a fresh and positive energy in the orphanage. You’ll also play the role of a friend and mentor to the children, turning them into confident individuals capable of believing in themselves. The love and attention that these children get from volunteers will uplift their spirits and put a smile on their faces.

Those are all actual statements combined from two different sites that sell volunteer trips to help orphans.

Think about it: these organizations are claiming that foreigners, who may or may not be appropriate to be around children, who may or may not have any experience working with children, who may not even speak the local language, should come interact with orphans, and that an ever-changing group of foreign volunteers, coming in for a few days or weeks at a time, can somehow transform the lives of vulnerable children. Or wildlife. The only thing those foreign volunteers need is the ability to pay all of their transportation, accommodation costs, and program fees to the trip organizer. No criminal background check, no verifiable, needed skills – just money and will.

There are so many Westerners ready to pay big bucks for these feel-good experiences and all the selfies they can take with third world children that many NGOs have popped up with fake orphanages: the children have parents, but the parents are given small fees by the NGOs for their kids to pretend to be orphans for foreigners.

Friends-International, with the backing of UNICEF, has launched this campaign to end what is known as orphanage tourism. This is from their web site:

Voluntourism can be a program that invites tourists (for a specific fee, or through an NGO directly recruiting), to volunteer at an organization. In most cases, these organizations do not require candidates to have relevant qualifications or previous work experience in social work or childcare. At worst, some organizations do not require or conduct proper background checks of volunteers before placing them in direct contact with children.

And then there is this incendiary report by South African and British academics that focuses on “orphan tourism” in southern Africa and reveals just how destructive these programs can be to local people, especially children. From the report:

The term ‘AIDS orphan tourism’, describes tourist activities consisting of short-term travel to facilities, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa, that involve volunteering as caregivers for ‘AIDS orphans’. Well-to-do tourists enrol for several weeks at a time to build schools, clean and restore river banks, ring birds and other useful activities in mostly poor but exotic settings… Well-to-do tourists enrol for several weeks at a time to build schools, clean and restore river banks, ring birds and other useful activities in mostly poor but exotic settings. AIDS orphan tourism has become a niche market, contributing to the growth of the tourism industry…

As in other countries undergoing social or other changes, non-family residential group care (orphanages) in southern Africa has expanded, perversely driven by the availability of funds for such facilities, and the glamour that media personalities have brought to setting them up. However, many orphanages are not registered with welfare authorities as required by law, and most face funding uncertainties and high staff turnover, making them unstable rather than secure environments for children. Moreover, children taken in by orphanages are usually from desperately poor families rather than orphans – the case of David Banda in Malawi is a case in point.

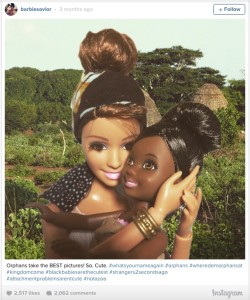

There is also this May 16, 2016 report from The Guardian that volunteers from the west are fueling the growth of orphanages in Uganda. Voluntourism has been linked to damaging local economies and commodifying vulnerable children. It also can perpetuate harmful stereotypes about the so-called “third world”, while also promoting neo-colonialistic attitudes. There’s also this blog from a person who paid to volunteer in an orphanage, and realized just how unethical it was.

A legitimate NGO serving orphans would never solicit come-one-come-all-as-long-as-you-can-pay volunteers via a general web site like Quora. Rather, they would have a proper, detailed Terms of Reference posted to credible humanitarian recruitment sites, like ReliefWeb or DevelopEx. That post for volunteers would detail the education and experience the volunteer would need to have and details on how the volunteers’ credibility would be investigated. And for legitimate programs, not every applicant would be accepted just because they’ve got the money to pay to the program organizer; in fact, many applicants would be turned away because they lack the necessary skills.

In short: unless a program overseas is recruiting volunteers who have many years of experience working with children, certifications, references and criminal background checks, has a web site that details how its programs are evaluated to show impact of their programs, and has endorsements by well-known international organizations, stay away from the program. And don’t be Savior Barbie.

As for supposed conservation volunteering in another country: why would legitimate wildlife sanctuaries allow untrained foreigners to work directly with wild(ish) animals for a few weeks? No credible zoo in the USA would ever do that. The Elephant Sanctuary in Tennessee doesn’t let volunteers interact with the elephants! Before you rush off to an animal sanctuary in a foreign country, do a tremendous amount of research to make sure this is truly a sanctuary, not a place that goes out and captures baby animals so that tourists will pay to care for them and have photos with them.

Update: a blog from 2015, where animal “help” becomes animal “torture”

“The ‘turtle conservation program’ was shut down after the police came (there is a law in Fiji to protect turtles as they are threatened by extinction). A girl made a… ehh… Let’s say critical Facebook post. I think ‘inhuman’ and ‘animal torture’ were some of the words she used… I’m just glad that I got my money back without any problem because I know about 7 people who had to go to court to get some of their money back because the agencies made a lot of great promises without keeping them. What they offer is not really volunteer work, here they call it voluntourism. A lot of money which doesn’t actually help anybody but just finances the international agencies. I got quite disillusioned about volunteering here. I left the volunteer house as soon as possible and went to a resort. The turtles were set free, but they are probably dead because they have been in the tank for too long and weren’t able to survive anymore. I’m so sorry for them.”

Update: a voluntourism / orphan tourism company is trying to fight back via Reddit.

July 17, 2017 update: Charities and voluntourism fuelling ‘orphanage crisis’ in Haiti, says NGO. At least 30,000 children live in privately-run orphanages in Haiti, but an estimated 80% of the children living in these facilities are not actually orphaned: they have one or more living parent, and almost all have other relatives, according to the Haitian government.

October 4, 2017 update: There is a long list of academic and institutional literature regarding international volunteering and orphan tourism, the risks to children, and how to prevent child sexual abuse. Here is an excerpt from one of the publications offered on this list:

Why are so many children placed in orphanages in countries like Nepal?

The initial rise in orphanages in developing countries cannot be attributed to the same

factors. Context specific history, poverty, natural disasters, epidemics (such as AIDS)

and conflicts are all things connected to the global rise in orphanages. However, in most

cases, one of the reasons that their numbers continue to grow is the availability and

willingness of paying orphanage voluntourists and well-intentioned charities that wish to

support orphanages and children’s homes. The funds which these individuals and

charities provide fuel the orphanage business. (Orphanage Trafficking and

Orphanage Voluntourism, Next Generation Nepal, 1 Apr 2014)

Also see:

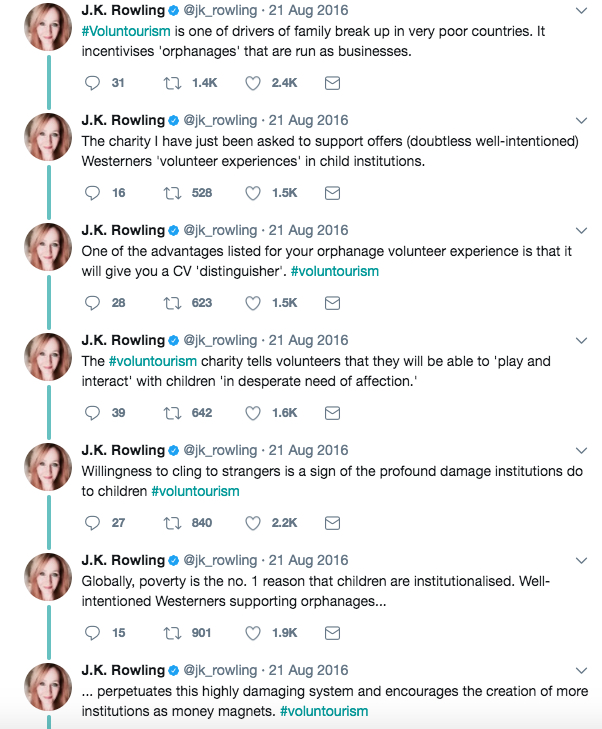

This, in short, is why I will never retweet appeals that treat poor children as opportunities to enhance Westerners’ CVs. #Voluntourism

This, in short, is why I will never retweet appeals that treat poor children as opportunities to enhance Westerners’ CVs. #Voluntourism